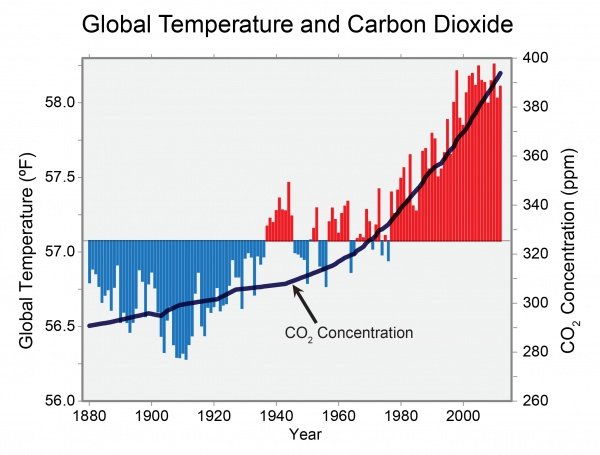

In early 2020 the effects of 1°C climate change are many; unprecedented wildfires, the second lowest amount of Arctic sea ice on record, and a winter that barely arrived. To avoid even larger impacts, the international community has set a goal of reducing carbon emissions to limit warming to 1.5°C, yet we are not on track to achieve this. The question is Why? To understand, it helps to review a bit of the history.

A few milestones in climate change science

The scientific study of climate change can be traced back to the 19th century, when it was first demonstrated that carbon dioxide and other gases were capable of absorbing heat. In 1896, Svante Arrhenius was able to calculate the extent to which increases in atmospheric CO2, caused by human activity, could potentially insulate and raise the earth’s temperature through the greenhouse effect.

Formal tracking of greenhouse gas increases started in 1958, when Charles Keeling began to make regular measurements of atmospheric CO2 concentrations. His data, known as the Keeling curve, shows sharp increases in CO2 year after year.

Fast forward to the eighties, which is the decade when the greenhouse effect really began to be felt.

The summer of 1988 was the hottest on record (up until then) and the US experienced widespread drought and wildfires. In June, NASA scientist James Hansen presented models and testified before congress that he was “99 percent sure” global warming was taking shape due to the greenhouse effect. Many experts point to 1988 as a critical turning point when the science of climate change took hold in the public consciousness. Six months later, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) was established.

So if we’ve known that the greenhouse effect is caused by increasing atmospheric CO2, and we’ve had decades of warming temperatures, why do CO2 emissions continue to increase?

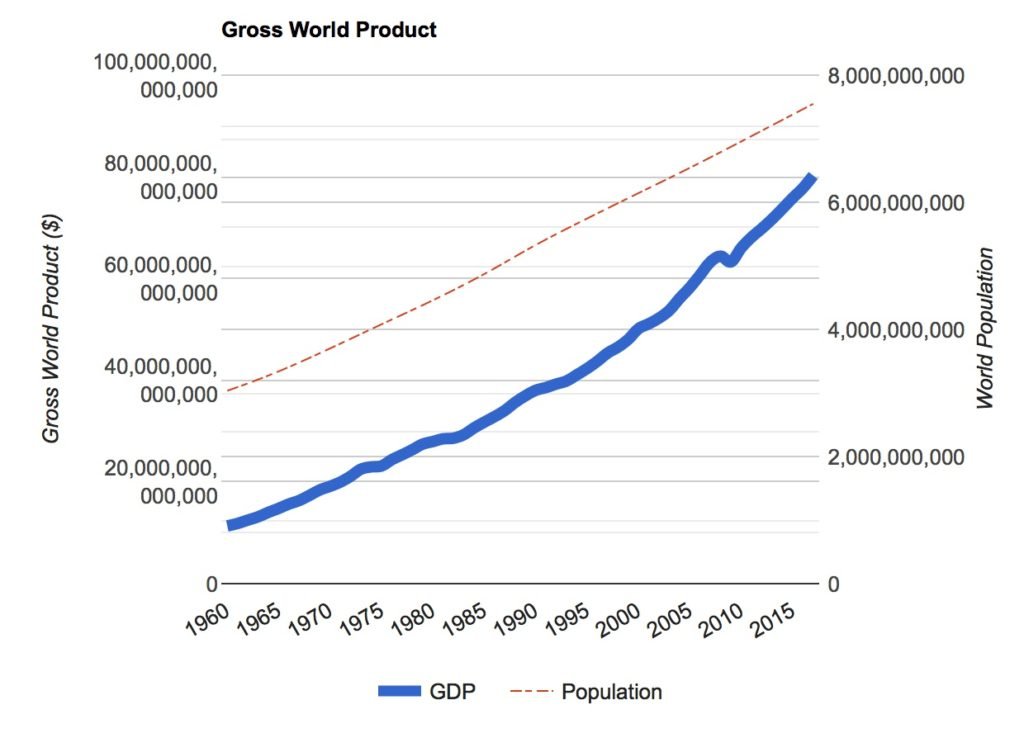

If you look at global population and Gross World Product as a measure of economic activity you see similar upward trends that coincide with atmospheric CO2 increases.

The world population and GWP nearly tripled between the years 1950-2010, as did the consumption of natural resources. In addition, rapid growth in urbanization, international tourism, ocean acidification, energy use, deforestation and many other things have occurred during this time, all driven by humans, in a period that has been dubbed the great acceleration.

Scientists have concluded the dramatic rise in atmospheric carbon is the result of human activity; primarily the burning of fossil fuels like gas, coal, and oil. Given that fossil fuels and GDP seem to go hand in hand (there is the perception that as economies grow, industrial activities increase which leads to more release of CO2 into the environment)- what does this imply for our economic future? Can we continue to pursue growth and protect the environment?

The pursuit of short-term growth has fueled inequality

It seems plain that during the latter half of the twentieth century, economic expansion led to improved health and well being for many. Particularly in the years following WWII, economic growth translated to rising incomes and greater equality for millions. However beginning around the 1980s, instead of moving people out of poverty, growth has led to greater inequality while being very destructive to the environment. This model is now being realized in heavily-populated places like China and India, which leads one to wonder if growth will always be able to improve people’s living conditions. Billions currently don’t have access to clean water, yet we are depleting world resources at an alarming rate.

While GDP as an economic measure was helpful in the past, many would argue the goal of an ever-expanding GDP is an outdated view. If we are to solve global issues like climate change, we need a new economic model. Enter the doughnut.

A new economic model that works for the planet

Current economic models largely ignore environmental impacts and thus economist Kate Raworth has developed a framework that incorporates the concept of biophysical planetary boundaries with human physical and social necessities that is shaped like, you guessed it, a doughnut.

From her book Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a Twenty-first Century Economist: “The diagram consists of two rings. The inner ring of the doughnut represents a sufficiency of the resources we need to lead a good life: food, clean water, housing, sanitation, energy, education, healthcare, democracy. Anyone living within that ring, in the hole in the middle of the doughnut, is in a state of deprivation. The outer ring of the doughnut consists of the Earth’s environmental limits, beyond which we inflict dangerous levels of climate change, ozone depletion, water pollution, loss of species and other assaults on the living world.”

“The area between the two rings – is the ecologically safe and socially just space in which humanity should strive to operate.”

So as opposed to ruling out growth, this suggests a sustainable economy operating within the doughnut is one that functions primarily to meet people’s needs without surpassing planetary boundaries. It also implies that in order to bring everyone into the “ecologically safe and socially just space”, our systems must be distributive. What is particularly helpful about her model is that it addresses planetary sustainability and social justice together in one framework, since many of these concepts interact with one another. It also allows one to visually grasp the areas in which humanity has already crossed the threshold of safe planetary boundaries.

Real change requires a new vision and not simply negatives to avoid. Prior economic models have set infinite growth as a target and relied on increasing GDP or ‘stuff’ to measure progress. While that goal may have been helpful when only 1 or 2 billion Homo sapiens existed, now that the population is rapidly approaching 8 billion, adjusting our economic expectations to living ‘within the doughnut’ may help us make better policy decisions to address urgent environmental issues like climate change.

“Instead of economies that need to grow, whether or not they make us thrive, we need economies that make us thrive, whether or not they grow”. K. Raworth